“That nothing is static or fixed, that all is fleeting and impermanent, is the first mark of existence.”

When I begin to think about why I paint, I am very much drawn to the idea of impermanence. For millennia, human beings have created out of a desire to leave a record of some sort; something beautiful or meaningful, artifacts of significance about themselves, the world and their beliefs. In some sense this is an exercise in futility, given the brief nature of our time here. In the end, all is fleeting, and great art, like everything else, will eventually fade away one day. But art can also be about that fading.

In Western Art, the vanitas tradition in 17th century still life painting of the Netherlands focuses on reminding the viewer of the brevity of life. Masters of the genre such as Pieter Claesz influenced their contemporaries, most notably Rembrandt, whose lifelong practice of self-portraiture bravely chronicled his own battles with Father Time. Skeletons and skulls, rotting fruit and wilting flowers, burning candles-- these obvious signs of decay and degeneration are proffered in a way that may now seem hackneyed to us. And yet the insistent display of morbidity, perhaps partly because it is so sumptuously rendered, nonetheless drives the intended points home: youth and beauty vanish, pleasures and riches are ephemeral, all is change.

Pieter Claesz Vanitas still life Oil on panel, 1630, 15.6” x 22”, The Hague

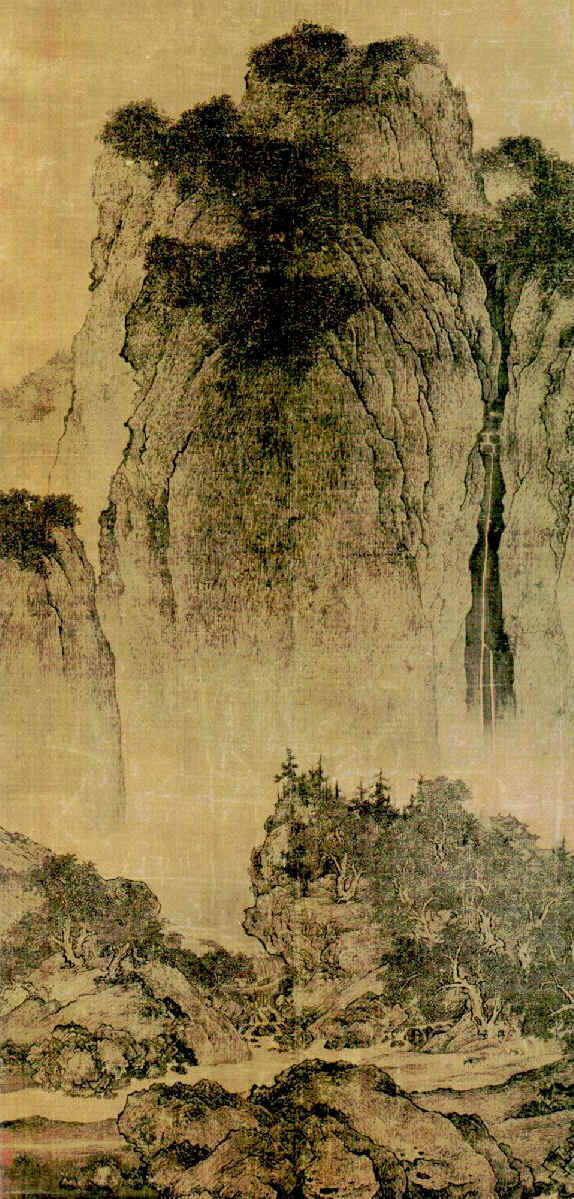

More implicitly, masters of the landscape tradition of Far Eastern Art such as Fan K’uan (10th-11th century) or Ma Yuan (12th-13th century), perceived the world quite differently. The abundance of Nature is revealed as an immense, inexhaustible space. And whereas the human observer in a vanitas painting is a priori, in many of these works that presence is diminished to the point of insignificance (one barely notices the figures in K’uan’s scroll). The Cosmos is not a fixed place where people and/or objects are metaphors for a path to self-improvement. Indeed, they are in constant flux and rendered inconsequential when placed against the sublime Void.

Several centuries and artistic inventions later, by the time we get to Impressionism and Cezanne, the perceived world has been torn asunder and dissolution is at the forefront of our visual experience. If, as Ezra Pound said, “Artists are the antennae of the race.”, then Cezanne’s feelers had to be on steroids. It wasn’t until my mid-forties that I began to actually understand the work, and I’m still unearthing its considerable depths. With Cezanne you see the individual characteristics of the world emerge and disband all at once.

Fan K’uan Travelers amid Mountains and Streams Ink on silk, hanging scroll early 11th century, National Palace Museum, Taipei

I believe that a great deal of post-Cezanne Modernist works can be read, indirectly or openly, as an inference to the impermanence of our world; the barely seen drift into the silence of Monet’s water lilies, a shrinking head in the vast space of a Giacometti portrait, the implied motion of a writhing nude by Francis Bacon, and the frenzied dynamism of de Kooning.

When I paint, mindful of and humbled by the great achievements of a long tradition, I am engaged in a process that has no utilitarian purpose other than to remind me of this impermanence so that I can live more presently and more fully in the moment.

Paul Cezanne Three Skulls Watercolor on paper, 1902/06, 18” x 24”, Art Institute of Chicago